Interview with filmmaker Ryan Killackey of Yasuni Man

At the International Primatological Society Conference, the JGI jungles of the Congo Basin interacted with the jungles of hundreds of other primate researchers and organizations. Along this primate journey, I met a filmmaker named Ryan Patrick Killackey, who is the producer, writer and director of a film called Yasuni Man, set in the Ecuadorian Amazon (He also coincidentally appeared in the PBS film EARTH a New Wild with our own Dr. JaneGoodall). Interested in the concept of how challenges to conservation overlap with challenges for people as depicted in his film, especially indigenous peoples, I wanted to know more. After seeing the film, I had a conversation with Ryan about what makes this film so singular and necessary, and what we can take from it for our own work to save these exceptional environments.

Growing up in Illinois, Ryan has always been passionate about wildlife, and spent summers in Michigan catching reptiles and amphibians. In his childhood, his father would wake him with a turtle or a toad he saved crossing the road on his way home from the night shift in Chicago, and his home was filled with creatures. While earning his degree in Wildlife Biology in Montana, he focused again on capturing wildlife, though this time through still photography. After volunteering for a time and becoming inspired by the ‘International Wildlife Film Festival,’ he chose to pursue a career in film. Ryan believes filmmaking is a wonderful art form, but is not for the weary. His advice: “It takes a lot of dedication and perseverance. Be careful, protect your stories, and stay dedicated to your craft.”

Read our conversation and to stream the film visit the links below:

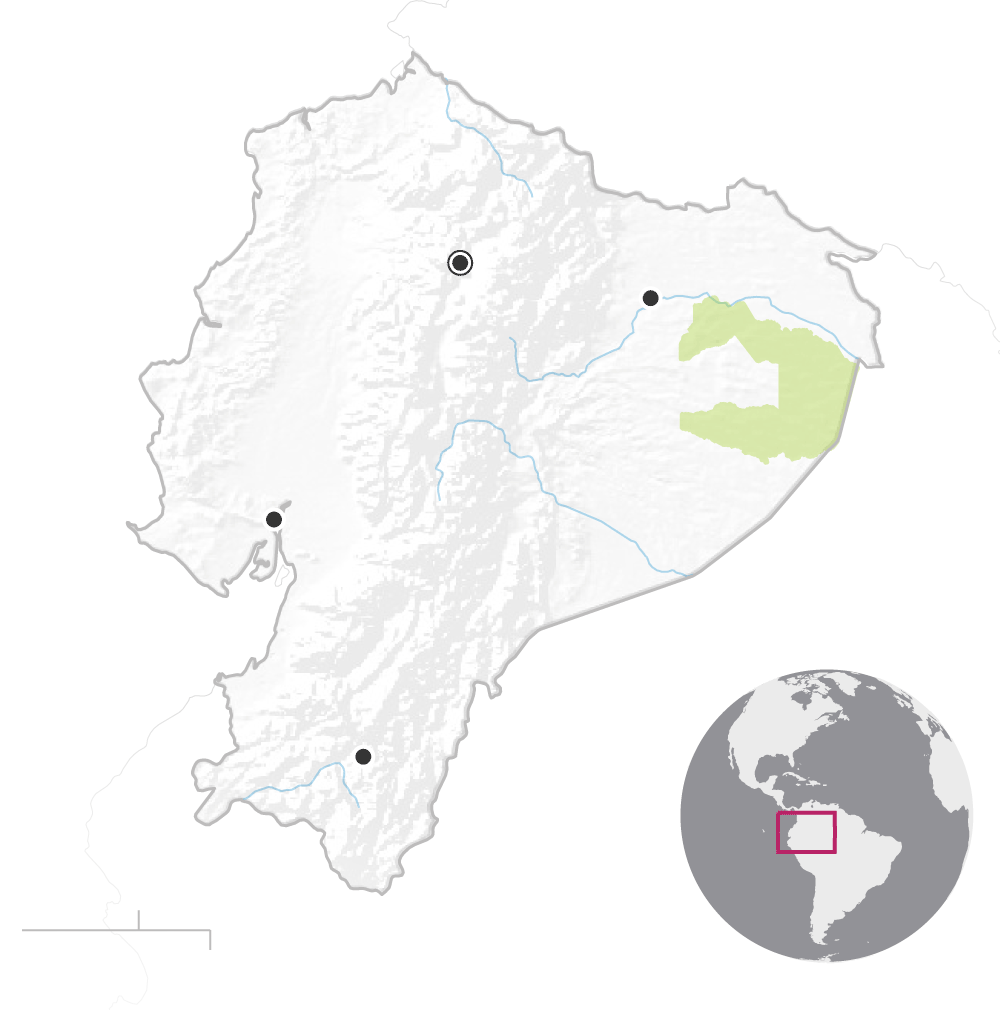

Map of Ecuador: Green area represents Yasuni National Park.Graphic: Jan Diehm/The Guardian

Ashley Sullivan: In the film, you present an aspect of your filmmaking that is unique – doing biological surveys of the area you are using as the subject of your story. Why do you think that is important and so special?

Ryan Patrick Killackey: This independently funded project increased the known species of Yasuni and gave a face to Yasuni’s rare biodiversity. Before my work, very few people had been to these regions, none the less done research or biological surveys in the core of the high conflict area that is Yasuni. There were only two places that had collected data prior: Pontifica Universidad Católica del Ecuador’s (PUCE) and Yasuni Biological Research Station and Universidad San Francisco de Quito’s (USFQ) Tiputini Biodiverstiy Station.

Photo by Ryan Killackey

Having unprecedented access was crucial in bringing the story of the biodiversity under this dense, dark canopy to life. We discovered new species, first records and several range extensions. I’m quite proud that a tiny project like mine is able to have this success with limited financial/no logistical support. (Only other orgs who conduct research like this: The Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago and Conservation International. )

AS: What’s your most intense or meaningful memory from the making of Yasuni Man?

RK: I gave myself entirely to this project, filming for 365 days between 5 visits over a 7 year period, so it’s hard to name just one. I’ve had some exciting wildlife sightings including jaguar, ocelot, harpy eagle, river dolphins, sloths, anacondas, tapir, black caiman, just to name a few. Capturing images of wildlife with camera traps – like a giant armadillo or the short eared dog – felt like I was a kid unwrapping a present. I also had many cringe-worthy experiences, like getting parasitized by amoebas, almost dying from food poisoning, nearly stepping on venomous snakes and having to pull bot fly larva from my leg!

Photo by Ryan Killackey

Spending time with the Waorani is definitely one of the most amazing opportunities that I will ever have. Being guided through this region and story of how missionaries and oil/logging companies exploited the people and forest was eye opening. One day walking with the Waorani as they hunt or forage is mind-bending, and I have made priceless, lifelong friendships.

Sadness, heartache and love were some of the biggest influences in post-production and the script of this film. Several of my film’s subjects and friends tragically have passed away, and the loss of my own family members is something that I still struggle with.

AS: Part of the film depicts horrific violence – a dynamic and complicated result of many factors. There were and are great costs that you witnessed and experienced personally. Has there been greater collaboration between the Waorani groups and other entities to do something about what is happening since the film?

RK: Yasuni Man is a very visceral film – not for the  weak of heart. Telling this story without violence isn’t possible, but I tried to tell it in a way that was as unbiased as I could, showing the relationships between all influencers. Yasuni is home to Ecuador’s last remaining uncontacted clans, the Taromenane and Tagaeri, who defend their territory and home. With expansion of the petroleum industry, subsequent forest destruction, and the influx of colonists and illegal loggers bottlenecking these groups, violent confrontation will only increase until the uncontacted clans are all but wiped out.

weak of heart. Telling this story without violence isn’t possible, but I tried to tell it in a way that was as unbiased as I could, showing the relationships between all influencers. Yasuni is home to Ecuador’s last remaining uncontacted clans, the Taromenane and Tagaeri, who defend their territory and home. With expansion of the petroleum industry, subsequent forest destruction, and the influx of colonists and illegal loggers bottlenecking these groups, violent confrontation will only increase until the uncontacted clans are all but wiped out.

Collaboration between Waorani communities is slight but improving. Many Waorani felt abused and unrepresented by the original governing body Nacionalidad Waorani de Ecuador (NAWE). Now, Penti Baihua of the Bameno Community established the political body ‘Ome Yasuni,’ that is a strong voice defending Waorani rights and territory, keeping NAWE and Ecuador’s government in check.

AS: What has been the best part of showing your film to people and telling the Yasuni story?

Photo by Ryan Killackey

RK: I always enjoy listening to the reactions of the audience. When they laugh or gasp at the right places, I know that I’ve done something right. Most of all, seeing that people are reacting positively to a message that is filled with so many different emotions, many of which are sad or depressing, makes me feel that there is hope for Yasuni. The screenings have also been a great place to start a dialogue and conversation about a subject that is very heavy that most people seem to want to avoid.

AS: What would you like people to think about or do after seeing a film with as many volatile and complex issues as Yasuni Man?

RK: Nearly 70% of Yasuni’s oil comes to America, specifically California. Yasuni Man forces people to understand their role in the destruction; our missionaries, our consumption and our oil companies. It’s hard to admit that you are part of the problem, but it’s the first step to making tangible change.

We’re in a political environment where we need to be more active in fighting for things that matter. With the election of an unstable president, climate deniers and fossil fuel exploiters in the congress and senate, we must be diligent and committed. Become informed, and contribute to caring for your fellow human beings, wildlife and environment.

AS: In the film, missionaries and oil companies brought a sense of “modernism” to the Waorani, which for some, feels welcome. Why do you think it is vital to protect the Waorani culture (or any indigenous group) and their relationship to their land for important biodiverse regions, and in general?

RK: Indigenous people have always been the greatest defenders of our planet, and most exploited group. Once the tie binding culture and environment is severed to exploit resources, rapid cultural erosion occurs until a hollow shell remains, and identity is lost. Given such pressures, many sell out receiving short term gains for the oil or timber, and their forest is destroyed. When the oil is gone (which in Ecuador will be soon), the Waorani may be left with nothing.

Image from Yasuni Man by Ryan Killackey

Many in our society are stuck in a cycle of profits and exploitation, in the name of “progress,” taking indigenous culture and nature for granted. Indigenous communities have a tremendous amount of wisdom about medicinal plants and animals, and other universally beneficial expertise. An immense amount of knowledge is lost because of the treatment of indigenous people and their forest.

We live on a finite planet, with many finite resources, and our human population is exploding. We cannot continue to go on if we don’t take into consideration our impact on indigenous people and forest biodiversity.

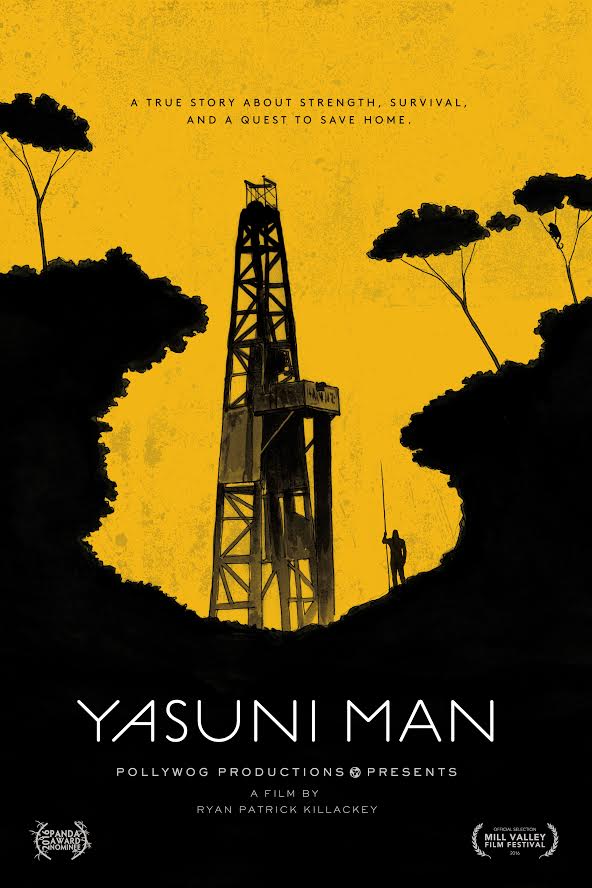

Yasuni Man is the winner of the “Silver Audience Award” from the Mill Valley Film Festival, the “Panda Award-Emerging Talent” from the Wildscreen Film Festival, and “Best Feature Film” from the NY Wild Film Fest.

Follow Yasuni Man on social media – Facebook, Twitter and Instagram: @yasuniman and to see more of Ryan’s work and Yasuni Man, check out his websites:

To see Yasuni Man, check out the following upcoming events + stay tuned on the Yasuni Man FB page for more:

Yasuní Man DC Premiere

Sunday, March 19th @ 7 pm

Landmark E Street Cinema

555 11th St NW

Q&A with the director and Moira Birss of Amazon Watch

$10 tickets available here

Yasuní Man film screening

and The Common Trees of Yasuní book signing

Wednesday, March 22nd @ 7 pm

The Lookout

2439 18th St NW

Q&A with the director and author Dr. Bejat McCracken

Event is FREE

The Common Trees of Yasuní book launch

Thursday, March 23rd @ 6 pm

Busboys and Poets – Takoma

235 Carroll St NW

With special guest, director Ryan P. Killackey

Event is FREE

Second screening of Yasuní Man

Friday, March 24th @ 12 noon

Watha T. Daniel Library

1630 7th St NW

Event is FREE